This is the first in a series of three articles looking at the future of design for the patient experience.

US Healthcare in Transition

The American healthcare system is out of balance: We spend too much and get too little for our hard-earned dollars.

Recent headlines have touted the fact that the growth of healthcare spending in the United States is actually slowing. This is according to a report published by Medicare in the journal Health Affairs in December 2014, which indicates that in 2013 healthcare spending grew by just 3.6% — the lowest year-to-year increase ever. But we need only dig a little deeper to discover that the overall news is far from rosy. According to that same Medicare report, healthcare spending is projected to grow 1.1% faster than the rest of the economy during 2013- 2023, with its share of the GDP rising from 17.2% in 2012 to 19.3% in 2023.

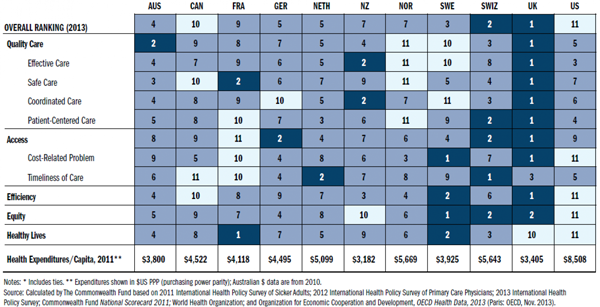

We certainly know how to spend money on healthcare, but what does it really buy us? According to a July 2014 report from The Commonwealth Fund healthcare think tank, not nearly enough. The 2014 update to its report "Mirror, Mirror, on the Wall", which rates healthcare across a variety of metrics — including quality, access, and efficiency — shows the United States lagging its 10 industrialized nation peers, while spending 50% more per capita than its closest competitor, Norway.

National healthcare rankings from The Commonwealth Fund

Healthcare administration certainly has our attention at a national policy level, contributing to polarizing partisan debate over the ACA. But the key to re-balancing the US healthcare delivery system and making progress toward reducing future costs, may lie in better understanding not its administration or even clinical care — while these both are important — but rather, the day-to-day needs of its patients.

Patient Experience as an Equal Factor

In software and other fields focused on the delivery of products and services, accepted best practice dictates that user experience, business and engineering play roughly equal roles. Each contributes to the bottom line and no one piece can really thrive without the other two. Conversely, in healthcare, while it may not be radical to say that the patient experience should have equal weight with the administrative / business and clinical factors, that view is far away from seeing real execution.

Health is one of just a few universal human needs: From the moment we're born to the moment we die, our health is at the forefront of our lives. Despite this inherent importance, the American system remains reactionary rather than proactive. From a service perspective, a quick survey of healthcare delivery reveals a system that first prioritizes the administrative and business aspects, and second clinical care, with the patient experience and patient / provider relationship placing a distant third.

Complex organizations, processes and systems combine to form what can only be described as an intimidating problem set. However, the bevy of problems from a patient-centric perspective are long standing and well known. For instance, long wait times at the doctor's office and long lead times for specialists are commonplace. Insurance-gated care translates into confusion over billing for patients and caregivers with little to no transparency into what procedures actually cost. Technology increases friction instead of flow, and does not facilitate better outcomes. It's no surprise that the overall healthcare experience from a patient perspective, to put it mildly, feels unfriendly and cold.

Add to this, on the patient side, a cultural bias toward lack of personal health responsibility coupled with little knowledge of personal health factors, and its little wonder that American healthcare delivery is overburdened.

If we desire better care, quality clinical experiences and good clinical outcomes for patients, we must contemplate designing for a complete patient experience — from process to system to built environment — that emphasizes usability, functionality, and even beauty. We must also find ways to measure and analyze the quality of experience over time, building upon and enhancing existing quality of care and quality of life metrics.

In this three-part blog series we'll examine the complex problem set contributing to patient experience, design approaches for improving it, and some real world examples from a software and technology perspective of attempts to improve it. Join us next week for part two.

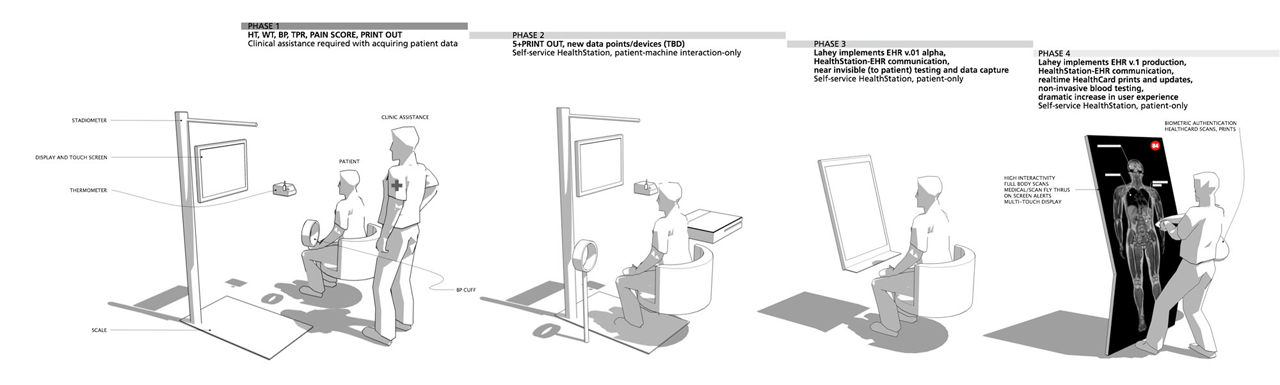

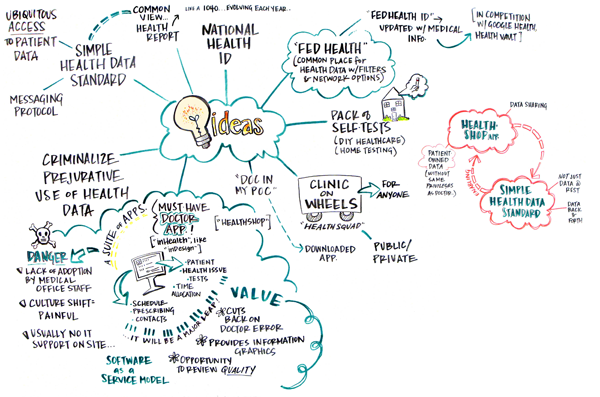

Ideas for health prototype candidates

Designing for Healthcare

If you're interested in further exploration of this topic, you might want to check out:

Health Reform 2.0: Envisioning a Patient Centered System

Health, Technology, and Design