This is the first in a two-part series on health literacy.

Most of us probably consider ourselves literate. More than that, we know how to read critically, ask questions about the content, apply what we learn to new situations, and maybe even teach it to others. So when you read the question in the title, what comes to mind?

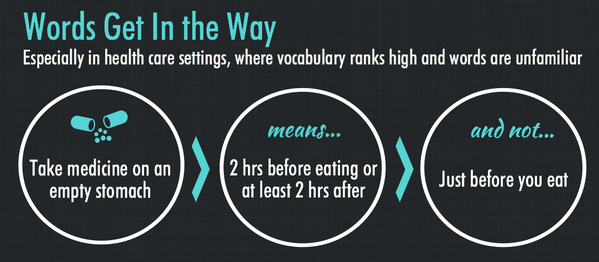

Here’s an example of how a common dosage instruction can be misunderstood. Do you know how to read it?

Source: Legacy Health Oregon and SW Washington Health Literacy Conference.

Being “health literate” is not simply about being able to read the words a prescription label. It requires fundamental knowledge, numeracy, critical thinking, and communication skills that enable you to understand what you read or are told and use that information to actively manage your own health. It even includes skills like navigating your health insurance plan features or searching a document for information.

Health literacy is not a new concern. In fact, the AMA has been working on raising awareness of our collective health literacy deficits since 1998. With the changes in health care delivery and who shoulders the costs, the roles of the obedient, trusting, deferential patient and paternalistic, all-knowing doctor have radically changed. With the burden of care shifting to patients and their families at home, low health literacy can be downright life-threatening. The New York Times stated “Patients with limited health literacy tend to be in poorer health, partake less frequently of preventive health measures and screening, and become hospitalized more frequently, resulting in an estimated annual cost of $50 billion to $73 billion.... [and] elderly patients with limited health literacy are almost twice as likely to die.”

Different Types of Health Literacy

According to the Healthy People initiative, heath literacy is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.” Simple enough—until you put it into context. Imagine a busy father with his toddler at the pediatrician’s. The child is screaming in pain, the dad is sleep-deprived and missing a meeting, and the doctor is hurrying to see her next patient. Will the dad remember to ask if the antibiotic being prescribed can be mixed with the baby’s juice, since he won’t take it any other way? Will it occur to him to ask the pharmacist? What about dosing every four hours, does that mean the child must be awakened during the night? Can he just use what is left of the old prescription that is sitting in the refrigerator at home so he can avoid the high cost of the new bottle? If the pain isn’t resolved in the next two or three days, what should the parents do next? When is surgery recommended? Will their insurance cover it? What if the doctor’s heavily accented English is difficult to understand? What is an in-network provider?

This dad is not someone you would expect to be health “illiterate.” However, any number of factors might contribute to his inability to ask the right questions, gather the right information, and speak up if he does not understand something. Like many parents, he may simply be embarrassed to ask, he may not trust the doctor, or he may assume that if something is important, the doctor will tell him. He may have poor numeracy skills or not understand the difference between brand-name and generic drugs. He could be dyslexic or have attention-deficit disorder. All or any of these reasons can prevent this dad from accessing the best care for his child and for himself.

According to a survey commissioned by consumer healthcare company iTriage, this dad is not alone. The survey found that nearly 42% of adults “never or only sometimes ask questions of their care provider, even when they don’t understand what they are being told.” Men are even less likely than women to ask such questions. Only a little more than half of the group surveyed knew when it is appropriate to seek care at an urgent care center. Of young adults, ages 18–24, only 38% could correctly identify when going to urgent care was appropriate (if their doctor’s office was closed). The report goes on to reveal similar problems in people’s understanding of insurance terms and policies such as deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance.

There are direct consequences of such confusion: higher costs to individuals and families, inappropriate utilization of health care resources, inefficiency, and waste. Of course, the costs can quickly escalate, if a patient is experiencing a life-threatening event but does not seek appropriate care.

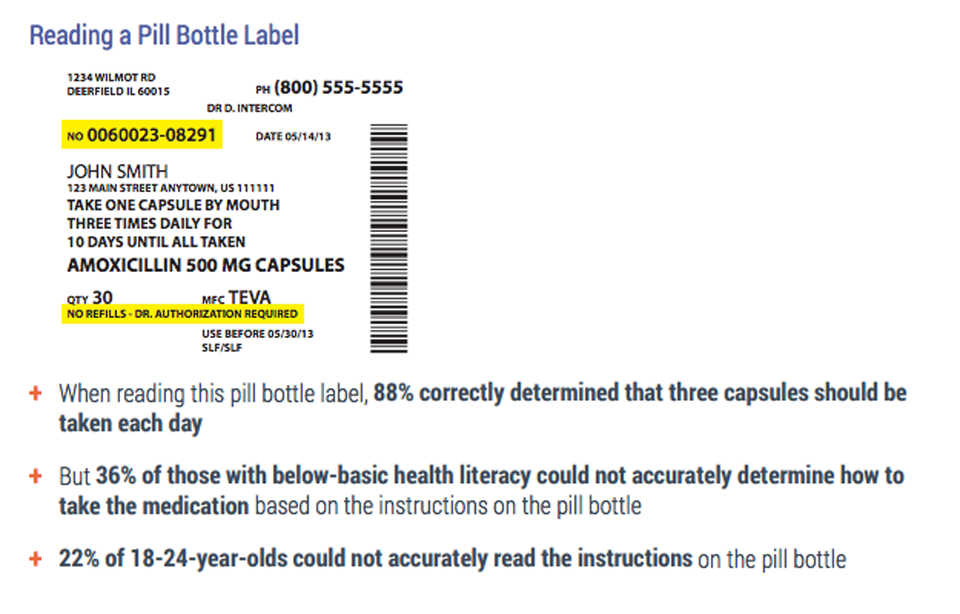

Let’s look at reading those prescription labels again, with an example from the iTriage report.

While more than 75% of the young adults surveyed could interpret the prescription instructions correctly, nearly a quarter of them were at risk of non-compliance at best, and overdosing at worst. That is far from optimal.

While more than 75% of the young adults surveyed could interpret the prescription instructions correctly, nearly a quarter of them were at risk of non-compliance at best, and overdosing at worst. That is far from optimal.

What Does Health Literacy Involve?

The National Assessment of Health Literacy is conducted every ten years in the US. It evaluates performance of tasks like the following to assess health literacy levels. (Source: The Best Medical Care: What Is Health Literacy?)

Below Basic Skills

- Circle the date of a medical appointment on a clinic appointment slip.

- Identify what they can drink before a medical test, based on a short set of instructions.

- Identify how often they should have a certain medical test, based on information in a simple pamphlet.

Basic Skills

- Give two reasons a person with no symptoms should be tested for a specific disease, after reading a simple pamphlet.

- Explain why it is difficult for people to know they have a certain chronic illness, based on a two-page article about the illness.

Intermediate Skills

- Determine a healthy weight range for a person of a certain height, based on a graph illustrating height, weight, and body mass index.

- Find the age range during which children should have a certain vaccine, using a chart that shows all the childhood vaccines and the ages children should receive them.

- Identify three substances that may interact with an over-the-counter medicine, based on information provided on the package.

Proficient Skills

- Look up the definition of a medical term by sifting through a complex document.

- Evaluate given information to determine what legal document could be of use in a specific health care situation.

- Calculate an employee’s share of health insurance costs for a year, using a table that shows how the employee’s monthly contribution varies.

Health literacy is a huge and complex topic, well beyond the scope of this article. However, it is important to be aware and informed about it, not only for our own health or that of our loved ones. As designers in the health care space, this is a fundamental problem that we must address in every medium. Next week, we’ll look at how we can contribute to improving health communication by addressing the appropriate design considerations and providing the right tools.