This is the third in a series of six articles looking at the future of experience design for emerging technologies — including the Internet of Things, robotics, genomics / synthetic biology, and 3D printing / additive fabrication. The first two articles were: The Future of Design: UX for Emerging Technologies and The Future of Design: UX for Genomics and Synthetic Biology.

More so than any other emerging technology, robotics has captured the imagination of American popular culture, especially that of the Hollywood sci-fi blockbuster. We’re entertained, enthralled, and maybe (but only slightly) alarmed by the legacy of Blade Runner, The Terminator, The Matrix and any number of lesser dystopian robotic celluloid futures. It remains to be seen if robot labor generates the kind of negative societal, economic, and political change depicted in the more pessimistic musings of our culture’s science fiction. Ensuring that it does not is a design challenge of the highest order. We must seek to guide our technology, rather than just allow it to guide us.

In the near term, robots are ideal for taking care of jobs that are repetitive, physically demanding, and potentially hazardous to humans. There are immediate, significant opportunities for using advanced robotics in energy, health, and manufacturing. Designers working in robotics will need to help identify the major challenges in these areas and seek proactive solutions — not an obvious or easy task.

We can see an example of these major challenges in the tragic events of the Fukushima meltdown. On March 11, 2011, a 9.0 magnitude earthquake and subsequent tsunami damaged the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactors in Japan. Over the course of 24 hours, crews tried desperately to fix the reactors. However, as, one by one, the back-up safety measures failed, the fuel rods in the nuclear reactor overheated, releasing dangerous amounts of radiation into the surrounding area. As radiation levels became far too high for humans, emergency teams at the plant were unable to enter key areas to complete the tasks required for recovery. Three hundred thousand people had to be evacuated from their homes, some of whom have yet to return.

The current state of the art in robotics is not capable of surviving the hostile, high-radiation environment of a nuclear power plant meltdown and dealing with the complex tasks required to assist a recovery effort. In the aftermath of Fukushima, the Japanese government did not immediately have access to hardened, radiation-resistant robots. A few robots from American companies—tested on the modern battlefields of Afghanistan and Iraq—including iRobot’s 710 Warrior and PackBot were able to survey the plant. The potential for recovery-related tasks that can and should be handled by advanced robotics is far greater than this. However, for many reasons, spanning political, cultural, and systemic, before the Fukushima event, an investment in robotic research was never seriously considered. The meltdown was an unthinkable catastrophe, one that Japanese officials thought could never happen, and as such, it was not even acknowledged as a possible scenario for which planning was needed.

An explosive ordnance disposal technician with the PackBot. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jhi L. Scott. This image was released by the United States Navy with the ID 090310-N-7090S-001.

The Fukushima catastrophe inspired the United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to create the Robotics Challenge, the purpose of which is to accelerate technological development for robotics in the area of disaster recovery. Acknowledging the fragility of our human systems and finding resilient solutions to catastrophes—whether it’s the next super storm, earthquake, or nuclear meltdown—is a problem on which designers, engineers, and technologists should focus.

In the DARPA competition mission statement, we can see the framing of the challenge in human terms.

History has repeatedly demonstrated that humans are vulnerable to natural and man-made disasters, and there are often limitations to what we can do to help remedy these situations when they occur. Robots have the potential to be useful assistants in situations in which humans cannot safely operate, but despite the imaginings of science fiction, the actual robots of today are not yet robust enough to function in many disaster zones nor capable enough to perform the most basic tasks required to help mitigate a crisis situation. The goal of the DRC is to generate groundbreaking research and development in hardware and software that will enable future robots, in tandem with human counterparts, to perform the most hazardous activities in disaster zones, thus reducing casualties and saving lives.

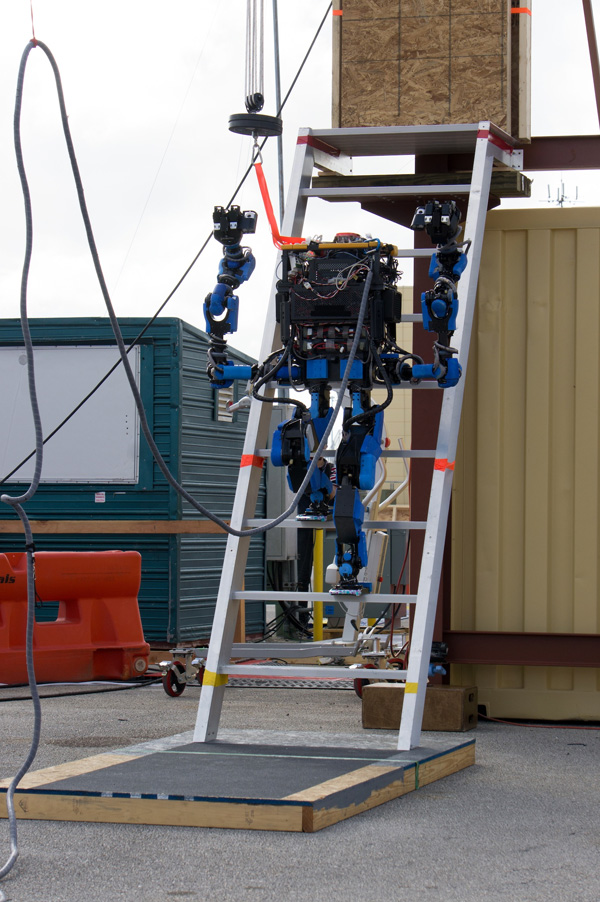

The competition, so far, has been successful in its mission to encourage innovation in advanced robotics. In the competition trials held in December 2013, robots from MIT, Carnegie Mellon, and the Google-owned Japanese firm, Schaft, Inc., competed at a variety of tasks related to disaster recovery, which included driving cars, traversing difficult terrain, climbing ladders, opening doors, moving debris, cutting holes in walls, closing valves, and unreeling hoses.

The Schaft, Inc. robot completing a task in the DARPA robotics competition.

The gap between the problems we face as a species and the seemingly unlimited potential of technologies ripe for implementation begs for considered but agile design thinking and practice. Designers should be problem identifiers, not just problem solvers searching for a solution to a pre-established set of parameters.We are on the cusp of a new technological age, saddled with the problems of the previous one, demanding that as we step forward we do not make the same mistakes. To do this, we must identify the right challenges to take on: the significant and valuable ones. Because this is where emerging technologies, like robotics, can have their greatest impact.

Designing for Emerging Technologies

If you're interested in further exploration of this topic, check out "Designing for Emerging Technologies", coming from O'Reilly Media this December, a project on which I was honored to serve as editor. In this book, you will discover 20 essays, from designers, engineers, scientists and thinkers, exploring areas of fast-moving, ground breaking technology in desperate need of experience design — from genetic engineering to neuroscience to wearables to biohacking — and discussing frameworks and techniques they've used in the burgeoning practice area of UX for emerging technologies.

The article header image is an algortithmically generated artwork, created especially for the "Designing for Emerging Technologies" project by Seth Hunter.